Written by an academic from another University for the campaign against the suspensions. It was written in advance of the suspensions being lifted but due its continued relevance and interest, we have posted it despite all students being reinstated.

Under the leadership of Vice-Chancellor David Eastwood, the University of Birmingham has gained increasing attention for the range of neoliberal disciplining measures it has introduced.

These include the decision in 2009 to propose the closure of the Department of Sociology. The initial proposal was for a reduction in the number of academic staff to 3 and the abandoning of a BA in Media, Culture and Society. Although a vibrant opposition campaign ultimately forced the University to opt instead to move Sociology into the neighbouring Department of Political Science and International Studies – and retain 6 members of staff – it nevertheless later made one of its few ethnic minority members of staff redundant in the process.

This has been part of a wider, and deeply unpopular, move within the University to use a new College structure as a means to impose a much more stringent focus on disciplining staff, most obviously under the guise of ‘performance management’. When the College system was introduced the local UCU branch presciently warned that this represented a possible move in the direction of ‘unfettered managerialism’, with “a danger that academic staff, rather than being treated as self-motivated creative professionals who are experts in their areas, will become work-units to be managed, ‘performance-managed’ and even ‘micro-managed’”. Indeed, in early 2013 this almost prompted a series of threatened strike days over redundancies and aggressive management practices, which were only called off at the last minute when the local UCU branch was able to agree a deal that would seek to impose limits on the management’s behaviour.

David Eastwood has played a major role in promoting these initiatives, while at the same time becoming currently the highest paid Vice-Chancellor in the country. He has also been one of the leading advocates of tuition fees (sitting on the Browne Review that initially advocated the lifting of a cap on fees in 2010), one of the leading advocates in the public debate that surrounded that initiative, and more recently proposing a further increase in fees.

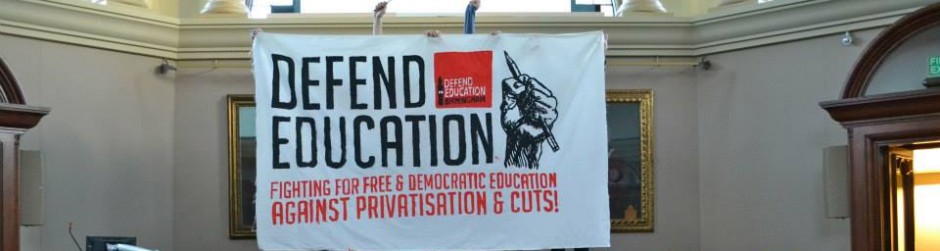

Given his controversial position, Eastwood has also faced considerable and ongoing student dissent throughout his time as Vice-Chancellor at the University of Birmingham. This has included calls for him to resign, repeated occupations of University premises, and national demonstrations. It appears that Eastwood has decided that the way to end this opposition is to come down hard on all forms of dissent. Indeed, there had in recent years already been a gradual move in the direction of repression – for instance, every elected student union officer for education (Guild of Students Vice President, Education) for the last three years has at some point also faced a University disciplinary hearing. This year, however, has seen exceptional levels of repression. 9 students have been put through a disciplinary procedure for protest-related activities, and 5 students have been suspended. 2 students remain suspended indefinitely, with no right of appeal, no access to the welfare provisions that students are normally entitled to, and with the very real possibility that they will have to repeat one year of their studies. In the case of the suspended students, therefore, this is clearly a punishment; but it is a punishment for a crime or act of misconduct that no students have yet to be found guilty of. Even if the students were reinstated tomorrow (which, sadly, is highly unlikely) the impact on their final year studies is such that they would already have been punished.

This approach should come as no surprise to anyone who knows of Eastwood’s intellectual trajectory prior to his entrance into management positions. Here it is useful to remind ourselves of the continued relevance of E.P. Thompson’s Warwick University Ltd, published in 1970 (and republished with new material in 2014) and highly critical of what he saw as the rise of the Business University. For instance, he concluded by asking:

Is it inevitable that the university will be reduced to the function of providing, with increasingly authoritarian efficiency, pre-packed intellectual commodities which meet the requirements of management? Or can we by our efforts transform it into a centre of free discussion and action, tolerating and even encouraging “subversive” thought and activity, for a dynamic renewal of the whole society in which it operates? (166)

Writing in 2000, Eastwood dismissed Thompson on the grounds that he suffered from ‘an acute case of that notable academic syndrome of conflating academic politics with global politics.’ (639). This mistake, in Eastwood’s eyes, led Thompson to, after resigning from Warwick, discard history research for peace campaigning. Eastwood ignores the fact that Thompson continued to combine academia and activism during the 1970s and 1980s. But the reasons for his critique lie elsewhere: the university should not be a place for politics as commonly conceived, for the university has a different role to play. Inevitably, this leads him to see universities in terms of intellectual prestige, and whose broader societal roles lie in how they ‘engage’ with the private sector.

Therefore, ‘academic politics’ revolves around how best to achieve the goals set by management, but not to consider the goals themselves or the undemocratic manner in which these goals are pursued (which would be the ‘wrong’ kind of politics). Ironically, though, Birmingham University embodies very clearly the continued need to connect ‘academic’ and ‘global’ politics, for the approach taken by Eastwood mirrors wider developments over the last several years. Political elites across the world have, in response to the post-2008 period of economic crisis, shifted to increasingly authoritarian ways of operating. This has led to many instances of the denial of political freedom in the name of ‘democracy’ and ‘prosperity’, ranging from: constitutional amendments in Eurozone countries mandating balanced budgets and therefore the continued degradation of public services; brutal police attacks on peaceful demonstrators in Turkey and Egypt; the Edward Snowden revelations about the huge expansion of government surveillance of our lives; and, in the UK, destructive ‘reforms’ of public services which were not mentioned prior to the 2010 election and the increasingly coercive policing of demonstrations and protests against them and wider political developments as well (including current proposals to introduce water cannon).

Therefore, the broader rise of increasingly authoritarian forms of neoliberalism are clearly expressed at the University of Birmingham. And herein lies the irony: as someone who has spent his whole career denying the relevance of ‘global politics’ for how universities operate, David Eastwood now finds his ‘academic politics’ to be demonstrably linked to the wider political context. The problem is that his responses to growing staff and student discontent, which are based upon the denial of this connection, are leading him into responses which leave his authority more fragile and more open to challenge.

Third Eye